Paper Link: Improving With Practice: A Neural Model of Mathematical Development

Contributor: Suyash Mallik

Introduction and Framework:

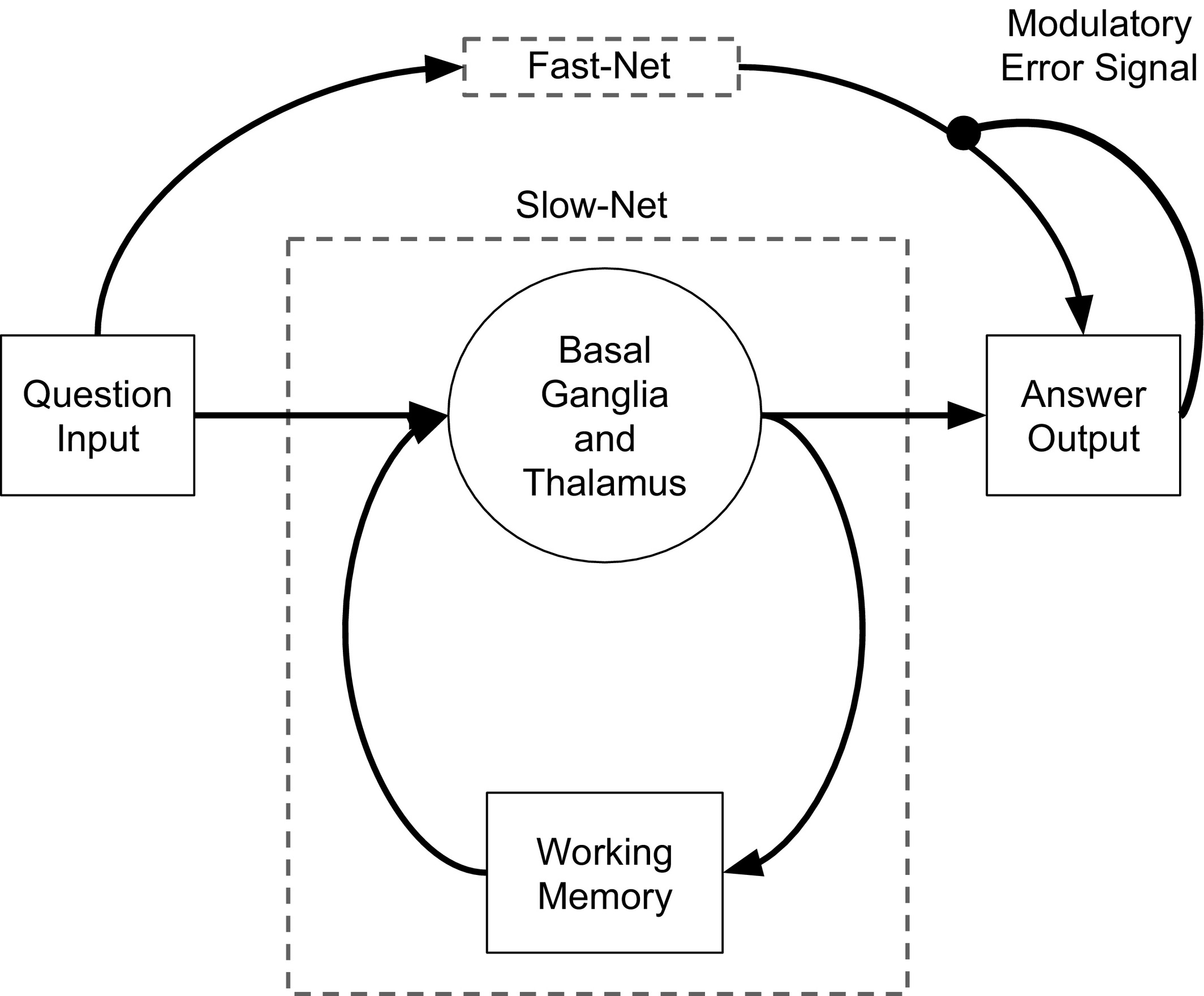

Scientists have used Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), to simulate the development of addition abilities in human brains. An SNN is the best model to simulate neurons, because it mimics the time delay present in propagation of signals in natural neurons. To simulate development of math skills, they used two neural networks, working in parallel - a slow network which performed the addition task by counting step-by-step, and a fast network which “memorized” and recalled the outputs of the slow network. The fast and slow networks largely correspond to different kinds of neurons: basal ganglia and cortical neurons, respectively. In humans, it is observed that these two strategies - counting and recall are the predominant strategies in the course of development of mathematical abilities in children. Mimicking the development of human children, the SNN model was found to start off by mainly using the counting strategy, but increasingly relied upon the recall strategy as it learned and got better. The scientists used the Neural Engineering Framework (NEF) to build the model, which uses vector spaces to perform simulated neural computation. In the NEF, groups of neurons act as mathematical functions on vectors. Using the NEF, vectors can be encoded (using encoding vectors) into sequences of firing times for a group of neurons, and the connections between these firing neurons transform the vectors, giving rise to computation. The encoding and decoding vectors of each neuron change as it learns to add (like natural neurons, which change in structure when learning a new skill).

Slow and fast networks, explained.

In this model, digits are represented by Semantic Pointers (SPs), which are neural, vector representations used in neural modeling to represent concepts, and the relationships between different concepts (using distances between vectors). Semantic Pointers are similar to pointers in computer science, as they can be “dereferenced” to access large amounts of information. While counting, the slow network uses a single population of neurons, with encoding vectors corresponding to the semantic pointers of each digit from 0-9. The neurons are connected such that they transform the SP of a digit to its increment.

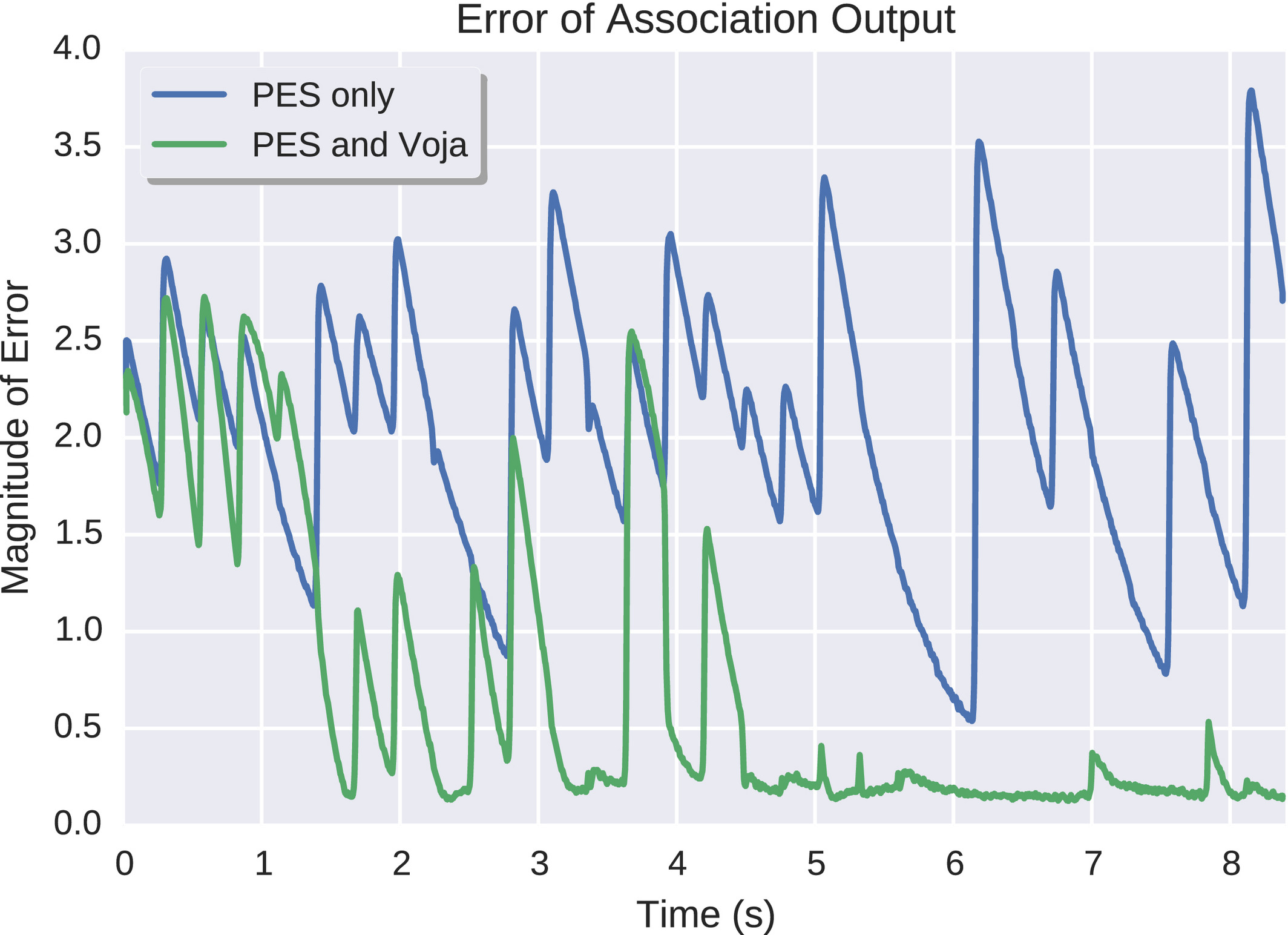

To implement the recall strategy effectively, the spiking neural network is subject to a supervised learning rule in conjunction with an unsupervised learning rule. Supervised learning is a kind of machine learning where the model learns from an existing “labeled” dataset, and is able to solve problems when faced with new, similar data. In unsupervised learning, the model analyses unlabeled datasets. The fast network uses unsupervised learning to understand the input (the two digits to be added) and supervised learning to retrieve the correct sum from the slow network.

Training the model, and conclusions:

The rate of learning (how much the model adjusts itself at each step of training) was chosen to be similar to that of cortical neurons in a human child’s brain. In order to decide which strategy (counting vs recall) the SNN would choose to present its final output, a separate set of neurons was constructed which relayed the output of the fast network, only when its relative error was less than 50%.

Upon training and testing the model, it was found that reaction time fell to a constant value as the SNN learned to rely upon the recall strategy. The same result was also found in human children, who added digits faster once they were confident with the recall strategy. The model also gave significant insights into the mechanism of dyscalculia, a learning disability where the ability to do math is hindered. People with dyscalculia are unable to use the part of their brains which performs the recall strategy effectively, and instead must rely on the counting strategy